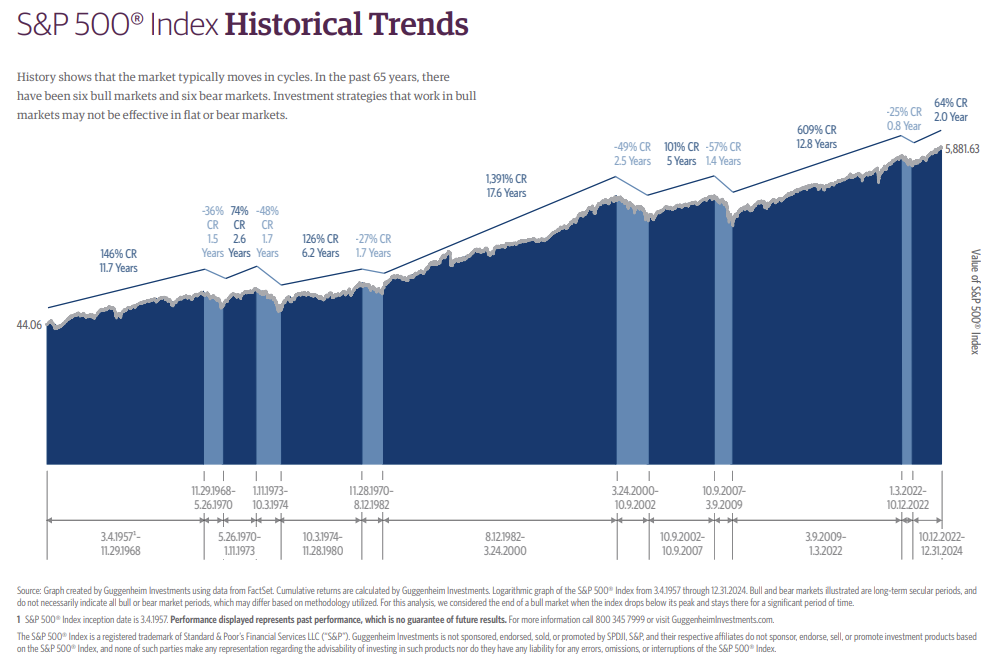

The S&P 500 fell nearly 50% during the 2000–2002 Tech Wreck, recovered to new highs, and then collapsed another 57% during the 2007–2009 Great Financial Crisis. Most investors view these as two separate disasters. They weren’t.

A more useful way to view this period is as a single bear market that followed the extraordinary 1982–2000 run. That bear began in 2000, sputtered during the mid-2000s rally, and wasn’t fully resolved until the investor wipeout and government intervention of the Great Financial Crisis.

From this perspective, 1982–2000 was a long bull market, and 2000–2013 (when the market finally regained its 2007 highs) was a long bear, despite multiple 20% declines during the earlier period and a more than 100% rally between 2002 and 2007.

These were secular market moves, not cyclical ones.

Secular Bull and Bear Markets

Cyclical markets are what investors focus on most. A cyclical bear is a 20% decline from peak to trough, while a cyclical bull generally refers to a rally that surpasses the prior peak.

Secular bull and bear markets are longer-lasting regimes. They include cyclical rallies and declines, but the dominant trend—up in a secular bull, flat or down in a secular bear—is not broken by those shorter-term cycles.

No one likes a bear market. Since 1980, the last six cyclical bears averaged declines of about 38%. But in a secular bull market, those declines become blips that reinforce the familiar advice to stay the course. They’re unpredictable, relatively short-lived, and the real mistake is getting out and missing the recovery. In that environment, holding works—and market risk is your ally.

But at some point, that typical advice won’t work and you need to take a long-term view of market history to prepare yourself for what I consider the biggest market risk right now – a prolonged, low-return period when this secular bull market ends.

Eventually, today’s secular upswing should give way to a prolonged secular bear. The last two—1966–1982 and 2000–2013—lasted an average of 14.5 years, during which stocks barely kept pace with inflation.

Fifteen years of flat, inflation-adjusted returns would pose a serious challenge for many investors. While we can’t—and won’t—time markets, we can prepare portfolios for that possibility. Thirteen years into the current secular bull is a reasonable time to start.

In a secular bear, you can’t rely just on U.S. stock market beta.

Investing In a Secular Bear Market

Here are several options, ordered by complexity:

Basics (easily implemented with index funds):

- Diversify internationally. The global stock market index didn’t formally exist during the 1966 secular bear, but during the lost decade (2000–2010), emerging market stocks delivered near double-digit annual returns. Developed international stocks, while less dramatic, still outperformed the S&P 500 by roughly 2.5% per year. See How to Invest in International Stocks for more specifics.

- Incorporate small caps. During the same lost decade, the Russell 2000 outperformed the S&P 500 by approximately 4.5% per year.

Intermediate (require research and or/help navigating options):

- Adjust U.S. stock exposure. The S&P 500 is heavily concentrated today in a small number of expensive growth stocks. If your equity exposure is limited to the S&P 500—or mirrors those same holdings—diversify. Strategies focused on higher-quality, cheaper stocks or high-quality dividend payers can be incorporated through value-based, factor-based, equal-weight, or similar approaches.

Advanced (work with an advisor):

- Incorporate other asset classes—carefully. Certain alternatives have performed well when stocks struggled during secular bear markets. The challenge is that this space is crowded with expensive products, back-tested strategies, and approaches that may not hold up in real-world conditions—or in the next secular bear. That doesn’t mean alternatives should be ignored, but they should be approached cautiously, vetted carefully, and used in modest allocations alongside the more fundamental steps above.

Conclusion

Short-term market declines are uncomfortable but familiar; long, low-return decades are far more damaging. Understanding that distinction—and preparing for it—may be the most important investment decision investors make today. Investing in a secular bear market requires broader diversification and more guidance than during strong bull markets.