Should You Sell Stocks Before the Election?

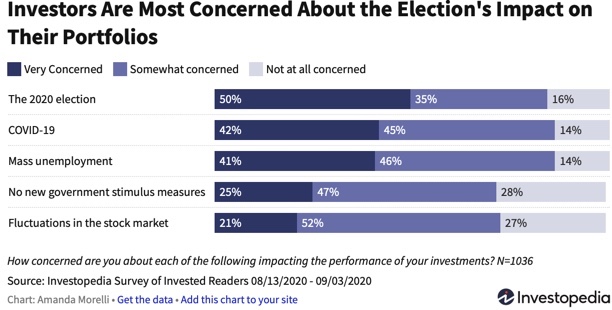

I’ve lately fielded lots of questions about selling stocks before the election to avoid a market crash. Whether it’s due to fears of election uncertainty, a delayed outcome, a contested transition of power, or which direction the eventual winner will take us, investors are concerned.

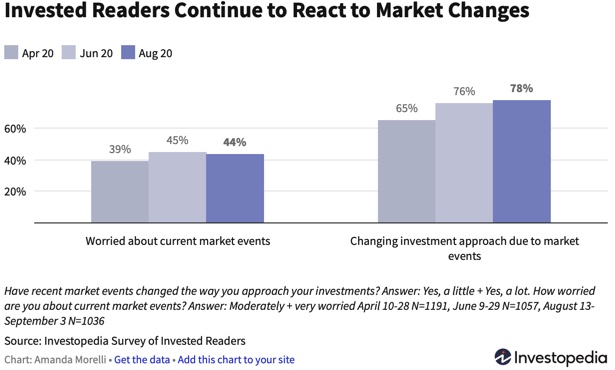

And they’re changing their portfolios.

What should you do?

Don’t sell stocks if you’re in the right portfolio for your situation

It’s a good idea to sell stocks if you’re going to need money sooner than planned from your portfolio.

However, if your situation hasn’t changed, and you have your long-term money invested in stocks, your short-term money invested in cash, and intermediate term money invested in a sensible mix based on the timing and amount of your withdrawals (per the rough guidelines below) stay the course.

Selling long-term investments for short-term concerns has costs. Trading costs, potential capital gains tax, and opportunity cost if your market timing prediction does not work. You need to stay invested to access the market’s long-term return.

Protect your portfolio. Just do it differently.

Build a portfolio linked to your financial plan for the best protection against short-term market uncertainty. Know your investment time horizon – both when portfolio withdrawals will be needed and how much, so you’re not forced to sell stocks at a loss to raise cash. A good wealth manager can build a financial plan and match your asset allocation to your expected cash-flow needs. Here are some general guidelines to follow yourself. (More about this here).

Short-term needs

Short-term is money you’ll need in the next three years, and it should be in cash. Find a high-yield savings account, set it aside, and call it a day.

Long-term needs

Long-term is money you don’t need for over 15 years. This is longer than you might think, but according to S&P 500 price history to be certain you won’t experience a market loss during your holding period, you should only have a 100% stock portfolio if your holding period is 16 years.

You can fairly consider this 16-year guideline as too conservative. For one, it’s the time period that has historically not lost money (past performance is no guarantee of future results). For an overwhelming majority of the time, 10 years is plenty. Secondarily, it was calculated by using only one group of stocks, albeit a broad one: US large company stocks. Including smaller company and foreign stocks should not require you to wait this long. However, international stocks don’t have as long a data set. If you want to use 10 years as your definition of long-term, I won’t argue.

Intermediate needs

By process of elimination, intermediate is money you’ll need in the next 4–15 years. When during that span you will need it and how much of it you’ll need should determine your allocation. These variables mean it won’t be as straightforward or precise.

I see two scenarios for how and when you might need this money: You’ll need all of it at some point, or you’ll need a certain percentage of it per year.

If you’re going to be cashing out the entire portfolio, I’d stick to the following ranges based on when you’ll need it:

- 4–5 years: 20%–35% stocks and 65%–80% bonds

- 6–8 years: 35%–50% stocks and 50%–65% bonds

- 8–15 years: 50%–65% stocks and 35%–50% bonds

If you’re going to have a steady withdrawal, I’d target the following asset allocation ranges for stocks with the rest being in bonds.

- Less than 4%: 65%–80% stocks

- 4%–5%: 50%–65% stocks

- 6%–7%: 35%–50% stocks

- Over 7%: 20%–35% stocks

Stick to your plan and don’t market time. If you’ve heard this before, it’s because it’s been said lots before, by me and others.

The great personal finance columnist, Jason Zweig, once described his job as “to write the exact same thing between 50 and 100 times a year in such a way that neither my editors nor my readers will ever think I am repeating myself.” That’s because while markets are always moving, the best advice rarely changes.

Approximately 99% of the time, the single most important thing investors should do is absolutely nothing.

Jason Zweig

Put the uncertainty risk into context

That advice is easier to digest when not in the moment. Sure, things seem unprecedented, with a range of uncomfortable potential outcomes. However, uncertainty can be overstated in stressful times. 2020 is a lot of things. Stressful tops the list.

We have regularly scheduled presidential elections every four years.

Either one of two parties will win that election.

The candidates have been public figures for most of their lives. Trump is 74. Biden is 77.

The campaign season is seemingly endless and longer than what we see in other countries. This election will clock in at 1,194 days by the time it’s over. “To put this into perspective, that’s equivalent to roughly 99 election seasons in Japan, where campaigns can only last 12 days by law” (check out this piece for more stats).

And at the risk of alienating every single reader, the economic policies of the two parties, while not similar, are at least recognizable to each other. By the time they get through Congress, they’ll be even more so.

Functioning markets have to be able to handle these things, and ours does.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying everyone will be happy the day after the election outcome is determined. But even that is predictable. The support for each party and for each candidate is well known. We’ve basically been a 50/50 country for the last twenty years. The popular vote margin in the last five elections has been 3%.

That’s not enough potential uncertainty for me personally to consider selling stocks before the election.

We can dig into this further with the help of a piece by CNBC’s Chief Senior Markets Commentator, Michael Santoli – Investors could be overplaying the election as a lasting driver of the stock market, history shows.

“In order to treat an election as a specific catalyst for investment moves, one would have to handicap the result, anticipate the makeup of Congress, intuit the key policy priorities, evaluate the likelihood of them becoming law, estimate their economic impact and then determine how much of this decision tree has already been priced into financial markets. Sound doable?”

Michael Santoli

It’s not. And the most recent example of this is Wall Street’s view that a Donald Trump victory in 2016 would be dangerous for stocks, and that his deregulatory policies would be best for the energy and financial sectors. Markets were strong until Covid-19, and those two sectors have been the worst performers since 2016 according to Santoli.

The piece further points out that there is not a material difference leading up to elections based on the ultimate winner. We do have to acknowledge that there may be some volatility if we have a delayed result. The last time we faced that was in 2000. However, potential short-term portfolio volatility is not reason enough to market time.

This isn’t to suggest the coming election can’t serve as a perfectly suitable excuse for further unsettled markets and rising investor risk aversion, now that the market leadership stocks have broken stride and the tape is in correction mode. But of all the relevant factors – a resolutely supportive Federal Reserve, fitful economic recovery, strong housing demand, corporate profits rising from depressed levels, investors’ willingness to pay up for secular-growth stocks – it’s unlikely the election will be the thing to make or break this cycle.

Michael Santoli

Our team at Heritage also addressed this in What’s Scarier than Coronavirus? Besides the planning and investment points made above, the piece highlights that institutional investors are also concerned. The 2020 election tops a Covid-19 second wave and a second wave of layoffs as their biggest investment fear.

SAID DIFFERENTLY, A REGULARLY OCCURRING, ONCE-EVERY-FOUR-YEARS, COUNTRY-SPECIFIC EVENT IS MORE CONCERNING TO SMART INVESTORS THAN A ONCE-IN-A-LIFETIME GLOBAL PANDEMIC.

Kristin Castner, CFA – Heritage Financial Services

The team’s advice?

- Don’t adjust your portfolio based on who you think will win. Historically, the political party in power does not by itself have a meaningful impact on long-term returns. Fidelity has a great article on why the economy and corporate earnings will always be more important drivers of future returns.

- If you have cash to put to work in the markets, don’t let the potential for market volatility keep you on the sidelines. A silver lining of market volatility is that buying stocks at a lower price generally equates to better future return potential. Read more about using a systematic approach to moving off the sidelines so you can potentially take advantage of buying in low.

- Don’t get out of the market just to shield yourself from volatility. This article from DiMeo Schneider & Associates reminds us that “some of the market’s best days happen during periods of heightened uncertainty”. This study by Putnam shows that missing the best 10 days of market performance for the 15-year period ending 12/31/19 would have reduced your total return by nearly 5%.

Then take a deep breath, because in two years it’ll start all over again!