We have a deficit and you know that you have to borrow to pay for the interest on the debt that you’ve had before and at north of four to five percent interest rates this is significant. It means you can have a snowballing effect. You have to borrow more and more. And you know that they’re not fixing the budget problem except verbally. ‘Hey, we’re going to fix the budget’…The structure of the political system unfortunately is driving us there…So this is one…main source of fragility that the political system is not adapted to that kind of thing.

Nassim Taleb – Living a Good Life in an Age of Volatility – Odd Lots Podcast

Throughout my career, deficit concerns have fueled market pessimism and caused investors to miss out on gains.

So, why write about the deficit today?

Despite the angst, we’re not doing anything about it, concerns are rising, and there’s stuff worth discussing, including why deficits are okay, what levels make sense, how we can narrow the deficit, and where tariffs fit into all this.

Balanced Budgets

Deficits are okay because it’s a mistake to treat the U.S. government like a household that must balance its checkbook. The Deficit Myth—reviewed here previously—makes this point well.

The U.S. is the sole issuer of the world’s reserve currency. It can’t go broke. This allows it to borrow at low rates and deficit spend to stimulate growth, support the economy, and invest in infrastructure and R&D.

Plus, the global financial system relies on U.S. Treasury bonds.

If the debt is affordable, a balanced budget doesn’t make sense.

The 3% Magic Number

You’ll often hear that a 3% deficit is “sustainable.” That’s because it roughly matches the economy’s growth rate, so debt won’t grow faster than the economy and our debt-to-GDP ratio will remain stable.

A stable debt-to-GDP ratio means an economy that can support its debt and happy investors and credit rating agencies. It also keeps interest costs from dominating the federal budget and crowding out other spending, much higher taxes, or deep spending cuts.

Using a personal finance analogy: if you earn $150,000 and have $450,000 in debt, your debt-to-income ratio is 300%. If your income grows faster than your debt, that ratio improves. But if your debt grows faster, it can become harder—or even impossible—to keep up with interest payments. That’s why mortgage underwriters focus heavily on debt-to-income ratios when deciding if someone can afford a loan.

GDP Isn’t Revenue

You may have noticed a potential disconnect in the analogy: for governments, we use debt-to-GDP ratio, while for individuals, we use debt-to-income ratio. For this to make sense, U.S. GDP needs to be correlated with federal tax revenue. If it weren’t, the 3% deficit target would rest on shaky ground. They are correlated, which is why whenever tax cuts are projected to increase deficits, proponents argue that the projections ignore the promised GDP boost. Peter Navarro made this case recently regarding the Big Beautiful Bill.

Deficit Concerns Today

We’ve run deficits above 3% in 29 of the last 45 years—and every year since 2016— and the new Big Beautiful Bill is projected to keep deficits well above 3%.

Debt levels will increase.

The debt-to-GDP ratio will keep rising just as concerns about it are rising, which we discussed on the podcast.

These thoughts from Jamie Dimon and Ray Dalio are a sampling of what’s out there. Dimon warned that the bond market could crack from unsustainable spending. Ray Dalio agrees.

The Deficit Math

There are two ways to reduce a deficit: more revenue, or less spending.

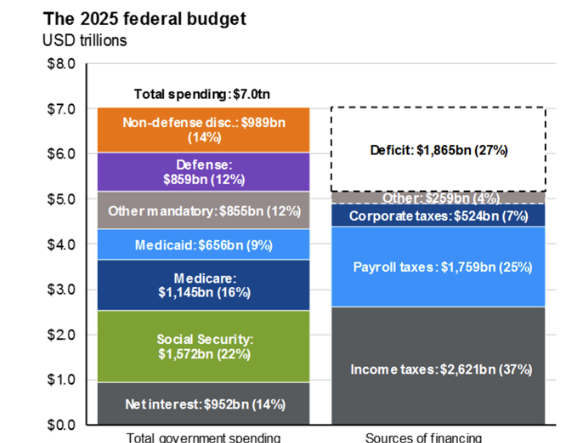

The 2025 deficit projection is 6.2% or $1.865 trillion. Getting to 3% requires cutting about a trillion dollars.

Looking at the chart below, our $7 trillion budget includes $1.807 trillion in interest payments and other mandatory spending. Then we add in $3.576 trillion for things politics won’t touch: defense, Social Security, and Medicare.

Now we’re at $5,383 trillion.

That leaves two categories, non-defense discretionary and Medicaid that you’d need to cut by 60%.

That’s one option.

I don’t see 60% cuts happening there, so now defense, Social Security, and Medicare are on the table.

That’s option two.

It doesn’t seem like there’s the political will or ability to cut enough in all these areas to get to a 3% deficit, so now we need more revenue.

That’s option three: A combination of across-the-board spending cuts, including entitlement reform and defense spending, and tax increases.

Of course, this all depends on your deficit and 3% target views. If you believe deficits are a problem, then deeper spending cuts or significant tax increases are needed. And if you think the 3% goal is too strict, only modest adjustments are required.

Things We Learned This Year

WMD

Remember Hans Blix?

He led the International Atomic Energy Agency and, before the Iraq War in 2003, was sent by the UN to search for weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. None were found—but his conclusions were ignored, and we invaded anyway.

I think about that whenever I hear claims that we can fix the deficit by rooting out fraud and waste. Elon Musk’s own “Blix” team—DOGE—spent months looking for it.

And what did they find?

Not enough to move the needle.

Maybe they weren’t up to the task. Or maybe there just isn’t enough fraud and waste to meaningfully reduce the deficit. I’m betting on the latter—and hoping we can move past this red herring and focus on real solutions.

Tariff Revenue

In Liberation Day Thoughts I wrote “it’s clear the administration wants tariff revenue. It’s not just about trade. They think the U.S. consumer keeps the global economy going, so they want to capture important revenue to help with deficits, future spending, and tax cuts. Therefore, it’s reasonable to assume higher tariffs are staying, and we won’t get an announcement completely reversing course after some trade wins.”

Nothing I’ve heard or read since has changed this. It’s confusing at times since tariffs are a blank canvas for this administration. People make whatever case for them they want. There’s still the group that insists this is about bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

But as Stephen Miran, Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors recently said on this podcast about the deficit and the Big Beautiful Bill “you have to be crazy to think that about $3 trillion of revenue from tariffs didn’t matter when discussing the outlook for the deficit.”

Revenue projections from tariffs vary widely, which isn’t surprising given that tariff policy remains unsettled. Still, some estimates suggest that a universal 15% tariff could raise between $1.5 and $3 trillion over the next decade.

I believe higher tariffs are here to stay. I don’t know how much that will impact the economy, and I expect companies to adjust and be fine. But it should help with deficits.