Protecting Your Portfolio From a Bear Market

Stocks provide patient investors with the potential for amazing long-term returns. A price you pay for those returns is stressful stock market volatility. Investors who can sit tight when their portfolio is down 20%, 30%, 40%, or even 50% reap the long-term benefits of owning stocks. Doing so is extremely difficult, but not impossible. Protecting your portfolio from a bear market comes down to understanding which market declines to worry about and which to ignore, positioning your portfolio correctly before bear markets happen, and holding on when they occur. It does not come from being able to forecast the next one.

Understanding Market Declines

Protecting your portfolio from a bear market starts with context on market declines and what protecting yourself from them looks like.

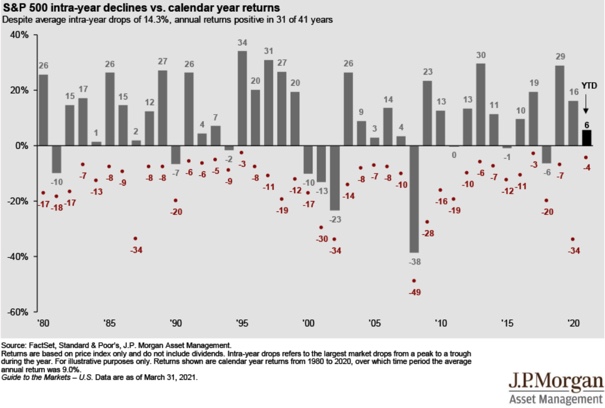

Market sell-offs happen. A stock market correction, defined as a decline between 10% and 20%, is practically an annual occurrence (see below). Despite the fact that in 30 of the last 40 years the S&P 500 was positive, on average it saw an intra-year decline of 14.3%.

We’re not trying to avoid an annual occurrence, so we’re going to ignore 5% – 15% market declines.

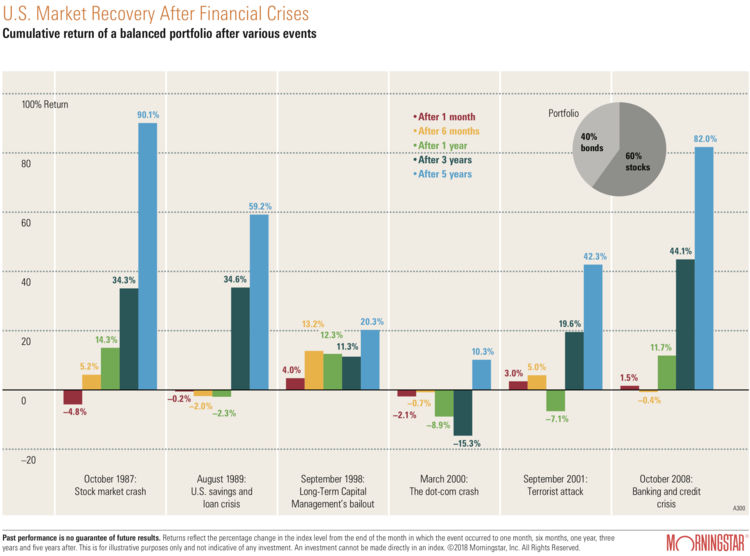

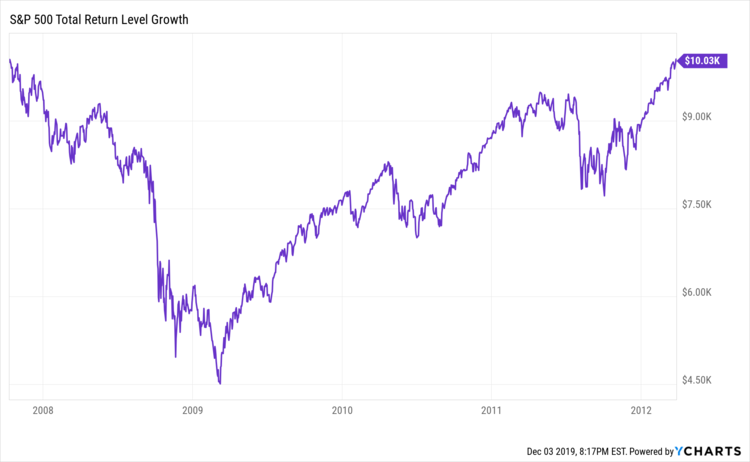

However, occasionally the markets drop more. 20% or more during those dreaded bear markets. Since the Great Depression we have had thirteen bear markets that declined on average 42%. They last on average less than two years. Putting aside the COVID-19 bear which lasted only four weeks, the bear market before that which began in October, 2007 lasted seventeen months. Three years after the market bottomed out in March, 2009 it had fully recovered.

Positioning Your Portfolio Properly

As I’ve said, the key to protecting yourself from these bears isn’t a crystal ball. Instead, make sure you’ve positioned your portfolio so that when they happen you don’t have to sell your stocks before the market recovers. Investors who stuck with a diversified portfolio through the four and a half year stretch above saw their portfolio recover and earn strong returns in the decade since the bottom. Investors who sold made a short-term loss permanent.

Your portfolio should not be invested in a vacuum. Whether or not you build a financial plan before investing, it’s important to know your time horizon – both when you might need money from your portfolio and how much, so you can invest appropriately for your time horizon and avoid having to sell stocks at a loss because you need cash. A good wealth manager can build a financial plan and an asset allocation that’s appropriate for your situation. If you are a do-it-yourselfer consider the following guidelines:

Short-term needs

Short-term is money you’ll need in the next three years, and it should be in cash. Cash is the only fully liquid guaranteed investment. CDs are guaranteed, but not liquid. Bonds are liquid, but not guaranteed.

Long-term needs

Long-term is money you don’t need for over 15 years. According to S&P 500 price history, in order to be certain that you won’t experience a market loss during your holding period, you should only have a 100% stock portfolio if your holding period is 16 years. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

You can fairly consider this 16-year guideline as too conservative. For one, it’s the time period that has guaranteed you no losses. For an overwhelming majority of the time, 10 years is plenty. Secondarily, it was calculated by using only one group of stocks, albeit a broad one: US large company stocks. Including smaller company and foreign stocks should not require you to wait this long. However, international stocks don’t have as long a data set. If you want to use 10 years as your definition of long-term, I won’t argue, but prudence dictates the extra years.

Intermediate needs

By extension, intermediate is money you’re going to need in the next 4–15 years. When during that span you will need it and how much of it you’ll need will determine your allocation. These variables mean it won’t be as straightforward or precise. You’re going to invest in stocks and bonds, not more than 80% stocks or less than 20%. Anything over 80% will be too close to the volatility of an all-stock portfolio, and a portfolio with no stocks can be riskier than one with a small amount.

I see two major scenarios for how and when you might need this money: You’ll need all of it at some point or you’ll need a certain percentage of it per year.

If you’re going to be cashing out the entire portfolio, I’d stick to the following ranges based on when you’ll need it:

- 4–5 years: 20%–35% stocks and 65%–80% bonds

- 6–8 years: 35%–50% stocks and 50%–65% bonds

- 8–15 years: 50%–65% stocks and 35%–50% bonds

If you’re going to have a steady withdrawal, I’d target the following asset allocation ranges for stocks with the rest being in bonds.

- Less than 4%: 65%–80% stocks

- 4%–5%: 50%–65% stocks

- 6%–7%: 35%–50% stocks

- Over 7%: 20%–35% stocks

Positioning your portfolio properly before a bear is key toward protecting your portfolio from a bear market. When the bear happens, you should not be forced to sell stocks at a loss to fund your lifestyle because your advisor has either built the appropriate portfolio for you, or you stuck to guidelines similar to the ones above.

Holding On During the Bear

So, we’re not reacting to modest market declines, and we’ve positioned our portfolios properly to help withstand a bear. The last step is how to react when that bear inevitable arrives. And for most, it’s the hardest step.

Investors have had a remarkably difficult time sticking to their long-term investment strategy.

Market volatility rattles investors’ nerves and exposes them to their biggest enemies – fear and greed. Fear during bear markets makes you jump out of the market when things are tough and turns short-term losses into permanent ones.

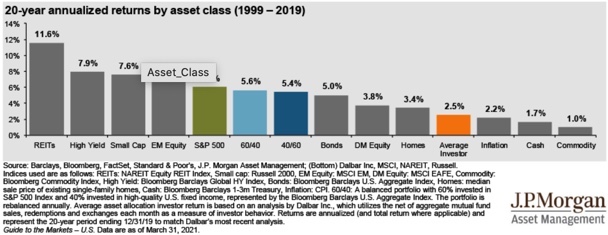

Investors have repeatedly done this. We can measure it in many ways. One of my favorite is the DALBAR, Inc. study that shows how investors have historically performed.

Because of poor investment timing decisions, like getting aggressive and buying stocks at the wrong time because everyone they know is making a killing in tech stocks (late 90’s), or selling stocks when everyone is afraid the world will end (2008), investors have struggled to earn decent returns.

To protect yourself during a bear market, be aware that your natural instinct to just do something when your portfolio is down is counter-productive. It locks in losses. It keeps you out of the market during the inevitable recovery.

Yet, sticking to your long-term strategy, much less buying more when stocks are cheaper, is difficult. And you will be tested when the time comes. And if it gets to the point where the charts aren’t helping you stay invested maybe this real estate analogy will help.

Real Estate Low-Ball Offer

Have you ever sold your house? It’s usually an emotional process involving many important steps:

1. Finding a realtor to guide you through a major transaction

2. Following their advice on repairs and updates to make the home salable

3. Deciding on a listing price after reviewing recent comparable transactions and market availability

4. Figuring out when to list

5. Creating the right marketing plan, including a write-up, photos, number of open houses, etc.

Then, the first offer arrives. You had a realistic asking price of $400,000, would have taken a bit less to get a deal done, but your realtor breaks the bad news that someone just offered $350,000 – 12.5% less than what your home is worth.

You’re ticked off. You tell the realtor that the lowball offer won’t work. Not only that, you won’t counter because the purchaser isn’t serious. You’re going to be patient and wait for the right offer from a realistic buyer.

I’m not a real estate professional, but I have been involved in enough real estate transactions (and seen clients go through many more) to know that the above scenario happens all the time.

Unless they’re in a jam, people don’t accept lowball offers on their house. They either ignore them, or find them offensive and dumb.

So, why do people seem to have the exact opposite reaction when the market starts making lowball offers on their portfolio?

Portfolio Low-Ball Offer

You take all the steps we’ve outlined above. You have the strategy in place and money invested in the right buckets. Then the market starts making you crazy offers for your portfolio. Unsolicited offers. At least with real estate, your home was for sale when the lowball offer arrived. Your portfolio is not for sale, yet the market is quoting you a price on it every second it’s open.

Sometimes you react to the price offers with amusement, perhaps telling your spouse or best friend how much you’re making. Sometimes you react to them with disappointment, hoping the prices will recover, but understanding that it’s a long-term game.

But when those real lowball offers come in, do you react the same way you would when someone wanted to buy your house for $50,000 less than asking price?

Nope.

For some reason, we’re much more willing to take seriously a market’s lowball offer on our portfolio than on our house.

We don’t get ticked off that the market is trying to scoop up our hard earned savings cheaply.

CNBC isn’t ignored because it’s not quoting serious prices.

Stress replaces patience.

We don’t get offended, we get upset.

We lose sight of the fact that we have built a thoughtful plan and portfolio strategy and start to give the lowballs much greater power over our financial wellbeing than they deserve.

It’s important to remember that the number of buyers and sellers in the market always matches up. So, when the market lowballs you, imagine that real estate buyer sliding an offer sheet across your kitchen table trying to buy your brokerage account and 401(k) for less than what they were recently worth – at a time they are not for sale! In my imagination, not only do you stick to your plan and say no, but you try and scrape together some cash and see if you can find someone willing to part with their hard earned investments in this fire sale.

Suggested Further Reading

Protecting Your Portfolio From the News